Food inflation shot up for the seventh successive month to 23.34% in September 2022 from 23.12% in August 2022. This is when food price levels in both months are compared with the prices in their corresponding months last year 2021.

At periods when food prices manifest not just as seasonal fluctuations due to planting and harvest times, but as more of structured price movements, as this, it is usually termed agflation, for its tendency to sway the direction of the headline inflation.

Top of this, since 2016, Nigeria has been battling with a vicious mix of high inflation, high unemployment, and slow economic growth, termed stagflation, a state of economic stagnation and high inflation.

The World Bank warned in June that, “if current stagflationary pressures intensify, EMDEs (Emerging and Developing Economies, like Nigeria) would likely face severe challenges again because of their less well-anchored inflation expectations, elevated financial vulnerabilities, and weakening growth fundamentals.”

Going by the strong pull of food prices on soaring inflation in Nigeria, solving stagflation would involve solving agflation.

For instance, a steepy climb in food prices pulled up the headline inflation (inflation on all items put together, food and non-food) from 17.6% to 20.77% this September.

Thanks for reading Data Dives from Dataphyte! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The September shift of 23.34% in food price levels is the highest since the 24.6% figure in October 2005, 17 years ago.

The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) highlighted likely factors responsible for these successive sharp increases in the annual inflation rate to include:

- Disruption in the supply of food products.

These disruptions are heightened by unprcedented floods across many states of the federation, which have destroyed farmlands, displaced rural farmers, and destroyed farm produce and food assets.

- Increase in import costs due to the persistent currency depreciation.

This impacts the costs of food imports and other non-food imports.

- General increase in the cost of production.

The above factors contribute to higher costs of transporting farm produce, greater volume of perished farm produce and scarcity at destination food markets.

Besides, increased costs of production result from higher cost of inputs in both agro-allied industries and hospitality businesses.

Beside households, hospitality and produce-dependent industries witnessed rising cost of staples including bread and cereals, potatoes, yam, and other tubers, oils and fats.

Analysing Agflation

Over time across the world, inflation has taken a meaning more serious than pumping air into a low-pressure soccer ball.

Today people readily see inflation as the rate of increase in the prices of products even when the products’ value remains the same or has even reduced.

For Nigeria, inflation rate has been on an upward trend since 2007.

Since 2005, the lowest annual inflation rates, at every second successive annual decline have been on the rise. The lowest rates rose from 5.4% in 2007 to 8.1% in 2014, and further to 11.4% in 2019.

Same with the highest inflation rates, at least at every second successive annual rise. The highest rates rose from 13.7% in 2010 to 16.5% in 2017, and further up to 17% in 2021.

Interestingly, agflation and stagflation rhyme and relate to inflation in its economic sense. But, beyond that, the morphology of the two words has less in common.

Agflation morphs up from agric + inflation, indicating inflation in the prices of agricultural products.

Generally, food and energy prices tend towards more rapid increases or decreases than other items. However, in Nigeria, energy prices have been relatively stable (compared to food prices) due to price controls on fuels, making food inflation the most prominent.

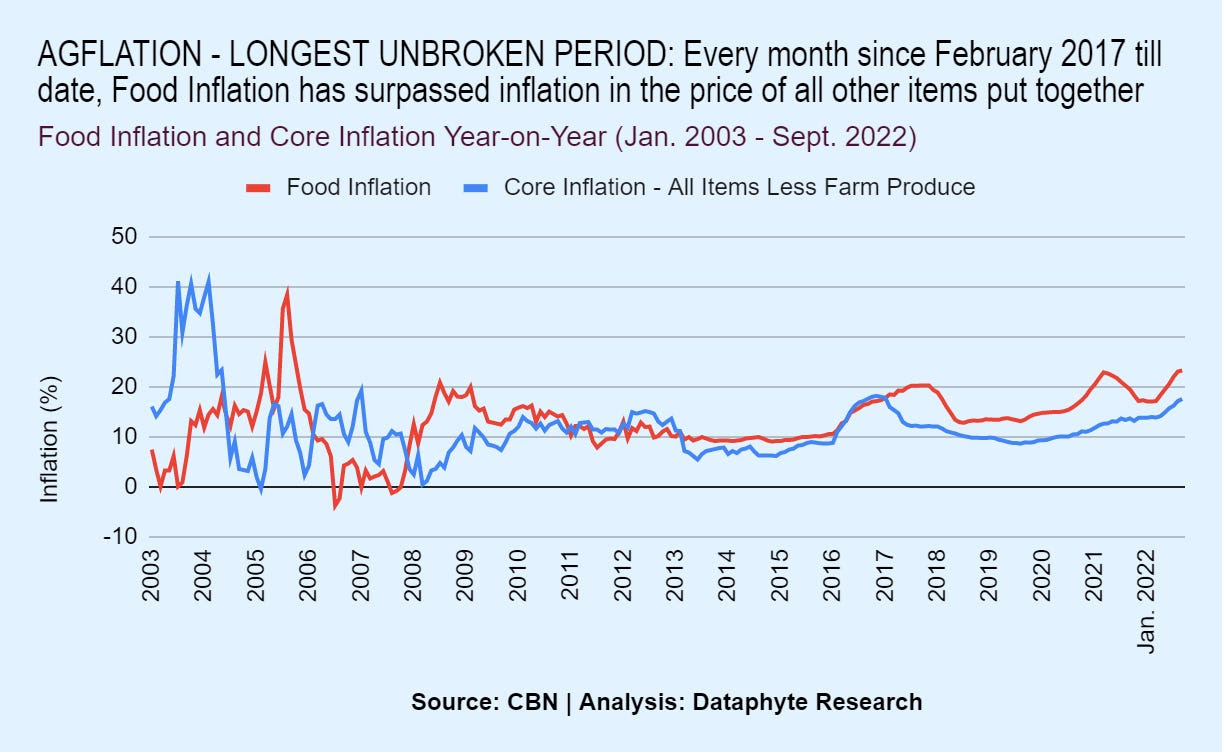

True to this pattern, in the last 20 years, food inflation in Nigeria showed a higher range (highest minus lowest value) of 42.2% above non-food inflation range of 41.6%.

Furthermore, the minimum (headline) inflation rate within the period was 3%, and the maximum was 28.2%, with a range of 25.2%.

While food inflation had the minimum value of -3.7%, core inflation had the highest value of 41.2%.

Yet, food inflation was highest in the last 20 years with an average of 13.3%. Core (non-food) inflation was 11.8%. Both made up to an average inflation rate of 12.5% within the period.

Of the 237 months reviewed, food inflation exceeded core inflation for 163 months.

More recently, food inflation exceeded core inflation non-stop in the last 68 successive months (February 2017 to September 2022).

Such systemic and ravaging agflation comes with attendant food scarcity, hunger, and nutritional deficiencies. This affects the poor the most, widens the poverty, and comes with attendant rise in crime.

Thus the next government at the federal and the state levels in 2023 ought to find answers for agflation, where previous governments and the incumbent have shown profound cluelessness in tackling the food price problem.

Answering Agflation

There are several playbook scenarios to tackle agflation, globally and countrywise. But then, there are circumstances peculiar to the Nigerian situation.

First, the NBS reported that, “On a monthly basis, food prices went up by 1.43%, slowing from a 1.98% rise in the previous month.

However, the NBS attributes the decline in food prices over the past two months (on a month-on-month basis) to a marked reduction in prices of some items like tubers, palm oil, maize, beans, and vegetables amid the ongoing harvest season.

Thus, the first answer to Agflation is to increase agricultural production. But, to increase farm output under the present circumstances, the government needs to sustain and encourage more rural-agricultural unemployment.

This requires the government to address the prolonged security for crop farmers and their farmlands, as well as secure livestock farmers from rustlers. Widely reported attacks of herdsmen, bandits and other terrorist groups on rural farmers and to the destruction of crops by their herds.

Where farms are secure, time-honoured practices for boosting production could create excess food supply that counterbalances the demand shortages, and force food prices down. In this regard, the World Economic Forum suggests 8 best practices for African countries:

1. Develop high-yield crops

Increased research into plant breeding, which takes into account the unique soil types of Africa, is a major requirement. A dollar invested in such research by the CGIAR consortium of agricultural research centres is estimated to yield six dollars in benefits.

2. Boost irrigation

With the growing effects of climate change on weather patterns, more irrigation will be needed. Average yields in irrigated farms are 90% higher than those of nearby rain-fed farms.

3. Increase the use of fertilizers

As soil fertility deteriorates, fertilizer use must increase. Governments need to ensure the right type of fertilizers are available at the right price, and at the right times. Fertilizer education lessens the environmental impact and an analysis of such training programs in East Africa found they boosted average incomes by 61%.

4. Improve market access, regulations, and governance

Improving rural infrastructure such as roads is crucial to raising productivity through reductions in shipping costs and the loss of perishable produce. Meanwhile, providing better incentives to farmers, including reductions in food subsidies, could raise agricultural output by nearly 5%.

5. Make better use of information technology

Information technology can support better crop, fertilizer and pesticide selection. It also improves land and water management, provides access to weather information, and connects farmers to sources of credit. Simply giving farmers information about crop prices in different markets has increased their bargaining power. Esoko, a provider of a mobile crop information services, estimates they can boost incomes by 10-30%.

6. Adopt genetically modified (GM) crops

The adoption of GM crops in Africa remains limited. Resistance from overseas customers, particularly in Europe, has been a hindrance. But with Africa’s rapid population growth, high-yield GM crops that are resistant to weather shocks provide an opportunity for Africa to address food insecurity. An analysis of more than one hundred studies found that GM crops reduced pesticide use by 37%, increased yields by 22%, and farmer profits by 68%.

7. Reform land ownership with productivity and inclusiveness in mind

Africa has the highest area of arable uncultivated land in the world (202 million hectares) yet most farms occupy less than 2 hectares. This results from poor land governance and ownership. Land reform has had mixed results on the African continent but changes that clearly define property rights, ensure the security of land tenure, and enable land to be used as collateral will be necessary if many African nations are to realise potential productivity gains.

8. Step up integration into Agricultural Value Chains (AVCs)

Driven partly by the growth of international supermarket chains, African economies have progressively diversified from traditional cash crops into fruits, vegetables, fish, and flowers. However, lack of access to finance and poor infrastructure have slowed progress. Government support, crucial to coordinate the integration of smallholder farmers into larger cooperatives and groups, may be needed in other areas that aid integration with wider markets.

These measures would boost local production, achieve significant import substitution, reduce food scarcity, and demand-pull and cost-push food inflation.

Analysing Stagflation

Unlike agflation, stagflation does not readily mean stag + inflation, which would have meant inflation in the price of every stag in the wild.

Instead, stagflation means stagnation + inflation. It indicates slow economic growth and high unemployment combined with rising prices and a decline in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of a country or state.

Between 1998 and 2015, Inflation and GDP growth fluctuated while Unemployment declined gradually from 4% in 1998 to 3.7% in 2013, and then rising to 4.3% in 2015.

However, since 2016, a totally different pattern unravelled as the unemployment rate began to rise consistently.

The rising unemployment rate coincided with rising inflation and the lowest growth rate. This led to the recession in 2016 and was compounded by the Covid 19 pandemic in 2020.

Despite the slow economic growth within this period, the country had always bounced back from its worst outings.

Nigeria’s 2017 Stagflation Mix

The outset of stagflation in Nigeria in 2017 could be traced to rising food inflation, declining agric GDP growth rate, and rising rural/agricultural unemployment.

- First, since February 2017, food inflation (agflation) has been the leading cause of inflation in the country.

- Secondly, sequel to the 2017 decline, successive annual growth in Nigeria’s Agric sector have been the lowest in the last 10 years (2012-2021).

Besides, natural causes such as drought, unpredictable rainfall, and recently, floods, have reduced farm output considerably. This has led to renewed fears of food insecurity in the country.

- Thirdly, since the fourth quarter of 2017 (2017 Q4), unemployment in rural areas began to exceed urban unemployment for an unprecedented 6 successive quarters.

Coincidentally, the last 5 years witnessed the height of attacks on farmers by Islamist groups, bandits and armed herdsmen, the same period rural unemployment rose.

This explains the decline in agric output growth as most of the fleeing and displaced farmers live in the rural areas.

- Also, it was in 2017 Q4 that the general unemployment level (along with rural unemployment) rose beyond the urban unemployment rate for an unprecedented 6 successive quarters, save 2018 Q3.

So, in Nigeria, stagflation is fuelled by agflation. Agflation is fuelled by declining growth in the quantity of farm outputs. And low farm output is caused by forced unemployment of fleeing and displaced rural farmers.

Economists think that stagnation and inflation ought to be mutually exclusive and so consider stagflation as a terribly bad economic situation for a country.

Answering Stagflation

Stagflation is currently a global issue, as countries trying to steady their economies after the economic turbulence during the pandemic now face renewed food and fuel import supply bottlenecks due to various sanctions agreements against Russian exports, due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Nigeria, like many other low middle income and heavily indebted countries, finds itself in a precarious situation.

While more stable economies roll out expansionary fiscal policies such as tax cuts, subsidies, and transfers, Nigeria is forced to increase taxes and cut subsidies to shore up revenues and service debts.

Nigeria could employ agile fiscal strategies tailored to “individual country circumstances”, as given by the IMF.

The following suggestions have been selected and adapted for Nigeria:

- In the economies hardest hit by the war in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia, fiscal policy needs to respond to the humanitarian crisis and economic disruptions.

Nigeria faces scarcity on several food imports from Russia and Ukraine. This led to unmet demand and higher prices of food imports such as Wheat.

The IMF suggests that, “given rising inflation and interest rates, fiscal support should be targeted to those most affected and priority areas.

- In nations where growth is stronger and inflation pressures remain elevated, fiscal policy should continue its shift from support to normalization.

This is where discretion on tax increases and subsidy matters. For Nigeria, subsidy on petrol has been a useless drain of revenue, and subsidy regimes and transfers in the country are fraught with corruption that robs the targeted low income earners to enrich the rich and powerful.

- In many emerging markets and low-income economies facing tight financing conditions or the risk of debt distress, governments will need to prioritize spending and raise revenues to reduce vulnerabilities.

To raise revenue (for priortised spendings), only taxes that target the rich could be raised. Tope Fasua suggests mansion taxes, property taxes, luxury taxes, capital gains taxes, and other progressive taxes aimed at high income earners.

- Commodity exporters that benefit from higher prices should seize the opportunity to rebuild buffers.

Also, it was observed that fluctuating inflation rates across the years from 1998 did not impact economic growth significantly, until the outset of scary unemployment levels in 2016. Thus, Nigeria’s answer for stagflation is to solve unemployment.

Furthermore, “Nigeria’s 2017 stagflation mix” shows that solving stagflation in Nigeria begins with solving rural unemployment.

Source: Dataphyte.

Secret Reporters No place to hide

Secret Reporters No place to hide