Given the heart-wrenching human rights records and cases of extra-judicial killings recorded under him, it’s debatable whether the late General Sani Abacha would end up in theists’ heaven. Many Nigerians who are victims of Abacha’s reign of terror would probably think of him now dwelling on the “other” side of heaven.

But in the last few years, no one has acted as Nigeria’s supportive “father in heaven” as much as Abacha has done, principally in terms of providing succour for a cash-strapped nation at its most critical point of need.

This week, the National Crime Agency (NCA) of the United Kingdom announced the recovery of yet another $23.5 million in looted funds from the allies and family the late Sani Abacha. The funds were retrieved as part of a wider pool of funds identified by the United States Department of Justice (USDOJ) as having been stolen out of Nigeria in the 1990s by Mr Abacha and his accomplices.

Before 1999, Nigeria had been ruled by 11 leaders: eight military heads of states and three civilians. Of the eight military heads of state, three are dead while five are still alive. Since 1999, the nation has also been governed by four civilian presidents, three of whom are still alive—and one is dead.

Yet among all of these leaders, Sani Abacha, the late head of state, has had the most notorious mention in the media in the last few years. Almost every year, investigators across different jurisdictions across the world often discover huge amounts of money linked to Abacha and allies.

“Relentless Giver”

Abacha ruled Nigeria between 1993 and 1998, when he died under mysterious circumstances. Since his death, every government that came after him has had to recover his loot from different jurisdictions. And word on the street is that he has been a “relentless giver.”

In an opinion piece published in a US publication in 2020, President Muhammadu Buhari made a tangential reference to recovery of the loot recorded under Abacha government, which he was a part of:

“And we can now move forward with road, rail and power station construction—in part, under own resources—thanks to close to a billion dollars of funds stolen from the people of Nigeria under a previous, undemocratic junta in the 1990s that have now been returned to our country from the U.S., U.K. and Switzerland.”

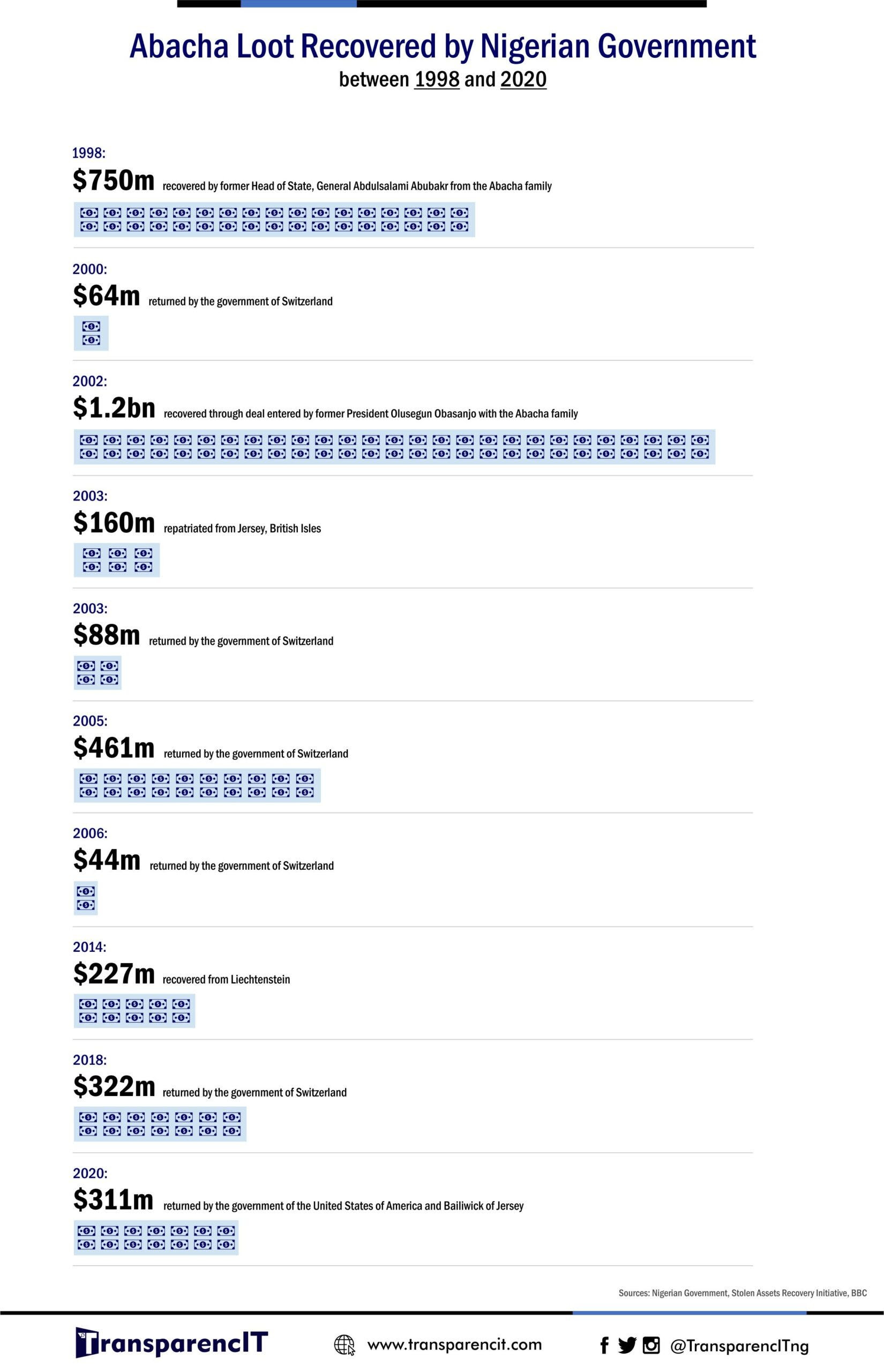

Meanwhile, a rough estimate of funds recovered from Abacha and allies since 1999, based on data crunched from newspaper reports, hovers around the region of $3.8 billion.

A TheCable report claimed that in 1998, Abubakar Abdulsalami, former military head of state, recovered $750 million from the Abacha family. In 2000, the report said, Obasanjo recovered $64 million from Switzerland; $1.2 billion in 2002; $88 million from Switzerland in 2003; and another $160 million from Jersey, British Island in 2003.

Between 2010 and 2022, the Jonathan and Buhari governments have equally recovered funds in the region of $1 billion.

Loot re-looted?

The plausible expectation of many is that the recoveries made from Abacha would help to shore up revenue shortfalls and bridge infrastructural gaps.

Last November, while speaking at a COP 26 high-level side event in Glasgow, President Muhammadu Buhari said the sum of $1.5 trillion is needed by Nigeria over a ten-year period, to achieve an appreciable level of the National Infrastructure Stock.

Yet since the Abacha loot recovery exercises have begun, the biggest fear remains that the loot may have been re-looted by government officials.

For instance, in 2020, part of measures put in place to ensure that a part of the loot isn’t re-looted was an agreement signed by the Federal Government, the government of Jersey and the United States to repatriate the latest $308m under certain stringent conditions. The agreement, signed by Attorney-General of the Federation and Minister of Justice, Mr. Abubakar Malami, detailed that the money be used to finance three major projects across Nigeria: Lagos-Ibadan Expressway (Western Region), Abuja-Kano Road (Northern Region), and Second Niger Bridge (Eastern Region).

The biggest fear lies principally in tranches of the loot being channeled toward programmes and policies designed to address the plight of poor and vulnerable Nigerians, which have been dogged with allegations of corruption and mismanagement.

Data sourced from the Africa Network for Environment and Economic Justice (ANEEJ) revealed that 703,506 poor and vulnerable Nigerians, out of an enrolled figure of 834, 948 targeted in the Nigerian social register, received a total of N23.742b from the recovered $322.5m Abacha loot returned from Switzerland as at December 31, 2019, under the Conditional Cash Transfer of the Social Investment Programme (SIP). But the SIP had been under attack, especially for lack of transparency and accountability.

Earlier in 2019, a total sum of $103.64m Abacha loot the government claimed to have disbursed became the subject of controversies amid allegations of corruption, poor accountability and shoddy disbursement mechanism.

So as Nigeria receives yet another $23.5 million in looted funds from allies and family of the late Sani Abacha, the big question remains: how much of this money would yet again be re-looted?

Saraki’s Tu-whit tu-whoo

Since he emerged the “northern consensus candidate” of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) alongside Bauchi State governor, Bala Mohammed, Senator Bukola Saraki has intensified efforts in his presidential campaign, proffering solution to a myriad of problems bedevilling Nigeria. Like an owl, he has been hooting wavering musical sounds into the ears of Nigerians.

Last week, Saraki promised free medical services to Nigerians if elected president, saying that he would leverage on his training as a medical doctor.

To be sure, Nigeria needs a total overhaul of its health infrastructure. In a first-of-its-kind Health System Sustainability index report released in March 2021, Nigeria ranked 14th with a total of 41 scores out of 18 African countries, with South Africa ranking first with 63 scores. Nigeria only improved slightly on the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) health system ranking from 187 out of 191 countries two decades ago to 163 out of 191 countries.

Yet in the midst of the poor records, concerns around funding remain fundamental. In 2019, the government said it would require a whooping sum of N1.08 trillion ($2.83 billion) to fix healthcare concerns alone.

The big question for Saraki remains: beyond picking up his long-abandoned stethoscope, how specifically does he intend to fund the deficit? Most importantly, in the context of Nigeria’s rural-urban inequalities and complexities, what constitutes “free healthcare”?

As the nation moves towards the 2023 polls, these are issues that must not be left muddled up in the typically Nigerian wild, wild field of bogus electioneering claims.

Ngige’s ‘System Reboot’

After claiming to have consulted with “mortal and immortals” ahead of the 2023 presidential election, the Minister of Labour and Employment, Senator Chris Ngige, finally announced his withdrawal from the race this week.

Since his withdrawal, many have opined that the minister was probably scared of the huge cost of electioneering. This could be a plausible reason, because Ngige had earlier lamented the huge cost of the APC nomination forms, saying his budget was N50m.

But a quick familiarity with data may also point to a more plausible reason.

Since he won the Anambra governorship election in 2003 and the senatorial elections in 2011, Ngige has had huge records in electoral misfortunes.

In 2013, Ngige who swept off the Anambra guber poll by Willie Obiano of APGA who scored 180,178 votes to win the election. In that election, Chris Ngige of the All Progressives Congress (APC) scored 95,963 votes to emerge third behind Obiano and Tony Nwoye of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) who scored 97,700 votes.

In 2015, while representing Anambra Central as a serving senator, Ngige lost the seat to a member of the House of Representatives, Hon. Uche Ekwunife of the Peoples Democratic Party, PDP.

In 2019, PDP presidential flag bearer Atiku Abubakar floored Muhammadu Buhari in all 21 local governments in Anambra, garnering 524,738 votes. An embarrassed Sen. Ngige faulted the election results. In the last governorship election, aside being edged out of the party, Ngige’s APC suffered massive defeat in the state.

In essence, Ngige’s reboots, as seen in his decision to withdraw from the presidential race, may have been informed by the nightmare of a looming defeat.

Like some people have opined, it may also not be unconnected with the fear of losing certainty for uncertainty, anyway. After all, remaining in a ministerial position for another 12 months can be more financially rewarding than embracing obscurity in the political trenches, with no prospect of victory.

Now, it does not matter if Minister Ngige has failed in its BASIC role of keeping lecturers in the classroom.

Source: Dataphyte

Secret Reporters No place to hide

Secret Reporters No place to hide